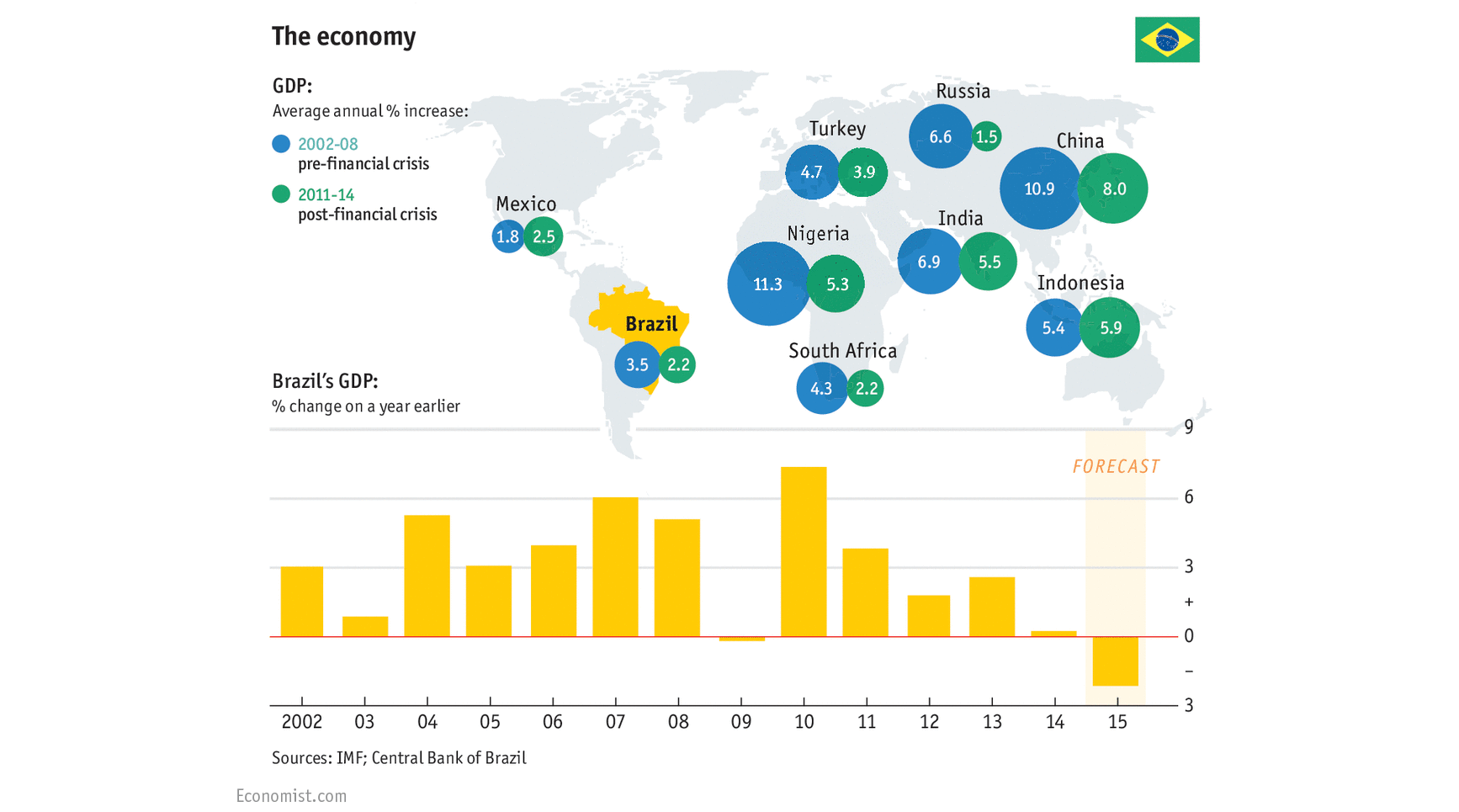

IN THE past few years, Brazil’s economy has disappointed. It grew by 2.2 per cent a year, on average, during President Dilma Rousseff’s first term in office in 2011-14, a slower rate of growth than in most of its neighbours, let alone in places like China or India. Last year GDP barely grew at all. It contracted by 2.6 per cent in the second quarter, compared to the same period last year, and is expected to shrink by 3 per cent in 2015. Household consumption has registered the first drop, year-on-year, since Ms Rousseff’s left-wing Workers’ Party (PT) came to power in 2003. At the same time, public spending has surged. In 2014, as Ms Rousseff sought re-election, the budget deficit doubled to 6.75 per cent of GDP (the bill has since swelled by another 2.5 percentage points). For the first time since 1997 the government failed to set aside any money to pay back creditors. Its planned primary surplus for this year, which excludes interest owed on debt, of 1.2 per cent of GDP is now expected to turn into a 0.9 per cent deficit. Brazil’s gross government debt of 66 per cent may look piffling compared to Greece’s 175 per cent or Japan’s 227 per cent. But Brazil’s high interest rates of around 14 per cent make borrowing costlier to service. Debt payments eat up more than 8 per cent of output. To let businesses and consumers borrow at less exorbitant rates, public banks have increasingly filled the gap, offering cheap, subsidised loans. These went from 40 per cent of all lending in 2010 to 55 per cent.

As the government loosened fiscal policy, the Central Bank prematurely slashed its benchmark interest rate in 2011-12. This pushed up inflation, which is now well above the bank’s self-imposed upper limit of 6.5 per cent, and way above its 4.5 per cent target. The interest-rate cut has since been reversed. On October 21st the Bank’s monetary policy-makers kept the rate at 14.25 per cent, nearly two percentage points higher than before the decision to cut. With inflation near double digits they cannot afford to loosen policy anytime soon. Alongside the lack of macroeconomic rigour, there was a lot of microeconomic meddling: the government pursued a clumsy industrial policy and shortchanged the private sector, for example by insisting on absurdly low rates of return on concessions to run infrastructure projects. Small wonder confidence slumped among businessmen.

Red tape, poor infrastructure and a strong currency have rendered much of industry uncompetitive. So consumers have been the main source of demand. A low unemployment rate pushed up wages. In the past ten years wages in the private sector have grown faster than GDP (public-sector workers have done even better). That allowed consumers to borrow more, which encouraged still more spending. Now the virtuous circle is turning vicious. Real wages have been falling since March, compared with a year earlier, mainly because Brazilian workers’ productivity never justified the earlier rises. People are returning to seek work just as there are fewer jobs to go around: unemployment, which has long been falling and dipped below 5 per cent for most of 2014, increased to 7.6 per cent in September. Economists expect it to reach 10 per cent next year.

To improve its finances the government is cutting spending on unemployment insurance (which had risen even when the jobless rate was falling) and on other benefits. Taxes, including fuel duty, are going up. So, too, are bills for water and electricity (two-thirds of which is generated by hydropower). The point is to reduce demand following a record drought in 2014 and to correct a policy of holding down regulated prices to keep inflation in check (and voters happy). But these increases have stoked inflation.

All this is hurting disposable incomes, a big portion of which are spent paying back consumer loans taken out in the good times. Consumer confidence has fallen to its lowest level since Fundação Getulio Vargas, a business school, began tracking it in 2005. The government has no money to boost investment. Petrobras, the state-controlled oil giant and Brazil’s biggest investor, is in the midst of a corruption scandal that has paralysed spending: the forgone investment may reduce GDP growth this year by one percentage point. It is hard to see where growth will come from.

Worst of all, Ms Rousseff’s policy levers are jammed. Failure to rein in spending already prompted Standard & Poor’s to strip Brazil of its prized investment-grade credit rating. Now economists fret that is may render monetary policy powerless: as interest bill balloons, the Central Bank could be forced to set rates to make it manageable rather than to keep prices in check. The hawkish finance minister, Joaquim Levy, has slashed 70 billion reais off the discretionary spending planned for this year (on top of the modest welfare reforms). But that is trimming around the edges: roughly 90 per cent of government spending is ring-fenced and needs congressional approval (or sometimes constitutional change) to curb. Nor can the Central Bank ease monetary policy: that would once again undermine its credibility and risk de-anchoring inflation expectations. If that were not enough, a depreciating real, which is oscillating around an all-time low, is adding to price pressures; it also makes Brazil’s $230 billion dollar-denominated debt dearer by the day. Ms Rousseff cannot bring Brazil’s animal spirits back to life with more spending and lower interest rates. She was hoping a return to economic orthodoxy would do the trick. Unfortunately, she lacks the political capital—and possibly conviction—to embrace it more fully in the teeth of congressional opposition to austerity. As a result, Brazil’s economy may take a while to heal.