by Ameera Fouad

After wild swings in the market, and after three days of falls after a sudden devaluation, China’s market was back to normal as the central bank raised the value of the Yuan.

Earlier this month, China’s main index of the stock market slumped 8.5 per cent in one day. The shock devaluation of nearly two per cent last Tuesday and the two subsequent reductions sent global financial markets into tailspin.

China marks the second largest economy in the world and its sudden wild swings raised questions and sparked fears of a possible currency war that the world might witness.

Pledging to seek a stable currency, the move was made by the People’s Bank of China (PBoC) which re-assured financial markets by raising the value of the Yuan against the US dollar by 0.05 per cent. China’s market regulator said, “it would continue to stabilise the stock market for a number of years”.

It said the role of the state-backed China Securities Finance Corp to stabilise the market would not change. However, it added that it would allow market forces to play a bigger role in setting stock prices.

The Yuan closed at 6.3912 on Friday, strengthening slightly from Thursday’s close of 6.3982.

Speaking earlier this week, another PBoC official said the central bank could directly intervene in the market, after reports it bought yuan on Wednesday to prop up the unit.

In China, it is believed that the central bank is fully capable of stabilising the exchange rate through direct intervention in the foreign exchange market.

Beijing prospects about Yuan is to push the currency to become one of the reserve currencies in the IMF (International Monetary Fund) in the SDR (special drawing rights) group and that is why it is keeping a tight grip on its currency and is protecting it from any outflows or inflows.

That’s the first major devaluation for China since 1994; the thing which fueled concern authorities who are combating a slowdown in one of the world’s largest economies. The Yuan changes impact both Asia’s growth prospects and the Federal Reserve’s interest rate policy as well as earnings at international companies from Caterpillar Inc. to Prada SPA.

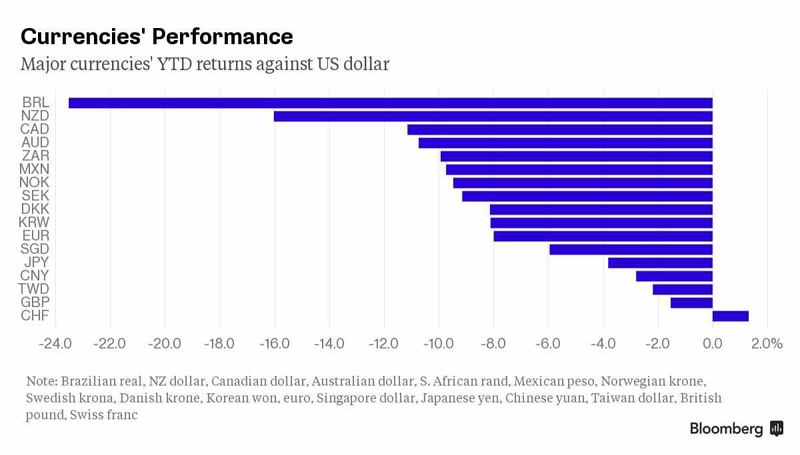

If such slumping rates had continued, dollar-denominated debt would be more expensive for Chinese borrowers, exacerbating capital outflows and putting pressure on export rivals to devalue their currencies.