At a time world media is looking into Egypt’s presidency elections through the binoculars of doubt and miss-guided reports, Egypt is leaping towards progress that has not only been recognised economically, but further praised by international reputed financial institutions, but Egypt is also developing Scientifically as a latest expedition developed by Mona Shahin, from Mansoura University Vertebrate Paleontology (MUVP) project, discovered a rare dinosaur fossil named “Mansourasaurus shahinae” in the Dakhla Oasis of the western desert in Egypt dating back to approximately 80 million years. Its name honors the town where the university is located, as well as Mona Shahin

Dinosaurs were the dominant species on Earth for about 135 million years (they existed for another 30-40 million years before that), and were the largest-known land animals to have ever lived. And yet, there are places in the world where their remains from certain time periods are not found, making it difficult for scientists to put together the puzzle of Earth’s geological and geographic history.

That is why the discovery of a rare dinosaur fossil, dating from the Late Cretaceous Period in modern-day Egypt has researchers excited. Fossils from about 100 million years ago to when the dinosaurs were wiped out nearly 66 million years ago are extremely rare to find on the African continent. Much of the land in Africa where the fossils could possibly be found is covered under dense vegetation, making it extremely difficult to look for.

The MUVP initiative organized the expedition that found the new dinosaur species. “The discovery and extraction of Mansourasaurus was such an amazing experience for the MUVP team. It was thrilling for my students to uncover bone after bone, as each new element we recovered helped to reveal who this giant dinosaur was,” Hesham Sallam, leader of the MUVP project, said in a statement Monday.

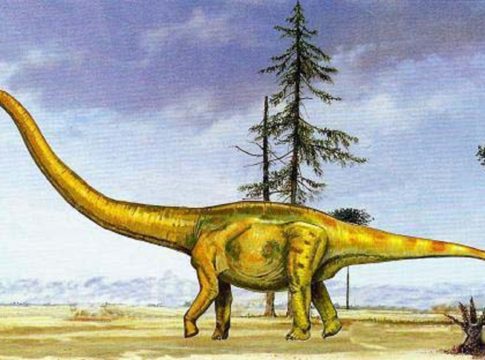

- shahinae was a titanosaur, the group of dinosaurs that include the biggest of them, like Argentinosaurus, Dreadnoughtus, and Patagotitan. But Mansourasaurus, which lived about 80 million years ago, was moderately sized for a titanosaur — only as large as a school bus and weighing as much as an African bull elephant. It had a long neck — a common feature among titanosaurs, who were all herbivores — and bony plates embedded in its skin.

The fossil is “the most complete dinosaur specimen so far discovered from the end of the Cretaceous in Africa,” according to the statement. Parts of the skeleton’s skull, the lower jaw, neck and back vertebrae, ribs, most of the shoulder and forelimb, part of the hind foot, and pieces of dermal plates, are all preserved. Matt Lamanna of Carnegie Museum of Natural History, a dinosaur paleontologist who coauthored the paper on M. shahinae, said: “When I first saw pics of the fossils, my jaw hit the floor. This was the Holy Grail — a well-preserved dinosaur from the end of the Age of Dinosaurs in Africa — that we paleontologists had been searching for for a long, long time.”

When dinosaurs first evolved in the Triassic, and even for quite some time after that into the Jurassic, most of the landmass on Earth was joined together in the supercontinent Pangea. But that had changed by the Late Cretaceous, and therefore, a comparative study of dinosaurs found in different parts of the world today can teach us about how and when the continents drifted apart, closer toward their present-day configuration.

Analysis of the M. shahinae fossil revealed closeness to other titanosaurs from Asia and Europe, and not so much similarity with other dinosaurs found in southern Africa or in South America. That led the researchers to conclude that a land link still existed between Africa and Europe at the time.

“Africa remains a giant question mark in terms of land-dwelling animals at the end of the Age of Dinosaurs. Mansourasaurus helps us address longstanding questions about Africa’s fossil record and paleobiology — what animals were living there, and to what other species were these animals most closely related? … Africa’s last dinosaurs weren’t completely isolated, contrary to what some have proposed in the past. There were still connections to Europe,” Eric Gorscak, a postdoctoral research scientist at the Field Museum and a contributing author on the study, explained.