By Khaled Amin

Libya was previously recognised as one of the greatest oil-producing countries in the world, Libyan immense resources had been put under severe risk ever since the 2011 uprisings and the fall of former President Muammar Al-Qaddafi’s regime.

Before the so called “Arab Spring”, Libya had relatively high living standards and accomplished economic growth, average citizens felt comfortable, and modern public services were provided by the government. Qaddafi established a profound long-term relations with many African nations, financially aided poor countries, and was a key player in finding vital African economic coalitions, which all presented Libya to be a potential major player in the MENA region.

Yet, the Libyan president’s internal oppressive strategies , rushed foreign policy, and tribal discrimination, had all put him and Libya under many worldwide animosity, and economic sanctions tightened-up opportunities of real expansions. But after the 2011 events… the expression “born with a silver spoon in their mouths” became no longer applied to Libyans, while growing acts of violence and intimidation, till these days of ours, being alarmingly frequent.

The power vacuum caused by the fall of the forty-year old plus rule, made it easy for armed militias to claim control over oil fields, and benefit from illegal trade through countries like Turkey and Qatar. The support NATO provided to armed “rebels” back then intended to make Libya a better place, but throughout more than 4 years of turmoil, the situation does not seem to be getting any better in the near future, as signs of “a second Iraq” appear to be familiar, with similar international community’s responses around both crisis.

Clifford Krauss, a New York Times reporter wrote back in 2011, “Colonel Qaddafi proved to be a problematic partner for international oil companies, frequently raising fees and taxes and making other demands. A new government with close ties to NATO may be an easier partner for Western nations to deal with. Some experts say that given a free hand, oil companies could find considerably more oil in Libya than they were able to locate under the restrictions placed by the Qaddafi government.”

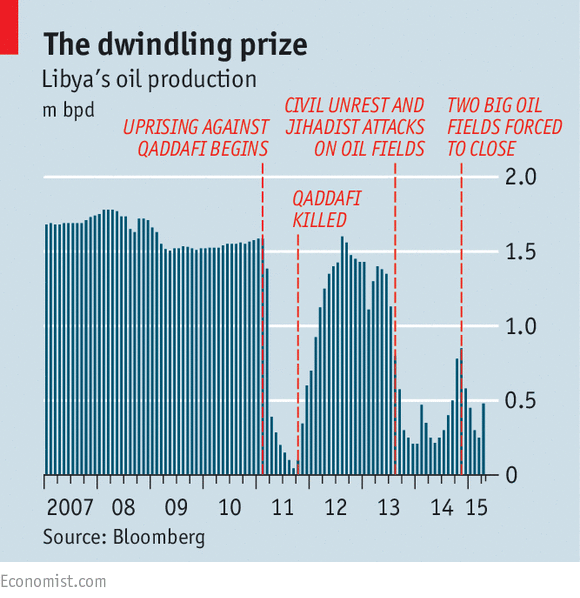

Libyan oil production foundered by more than half, from 1.7 mn barrels per day (bpd) at its pre-Qaddafi- fall peaks, to less than 500 bpd post-Qaddafi-fall, as shown in the graph. That, in turn, affected many major European oil importers like Italy, France and other powers who directly interfered in the conflict by dismantling Qaddafi’s forces and supporting rebels, giving compelling evidence that Libyan oil is under threat of being put to waste through black-markets and under-table agreements, as fears of Libya’s economic ruin deepened.

Luckily, earlier this year, the recognised government of El-Beida, made a grab for the country’s finances after controlling the state-run oil company, National Oil Corporation (NOC), and started transferring the NOC’s income to the government’s off-shore accounts, instead of the Central Bank in Tripoli (Controlled by a government allied with Islamists).

The Economist reported earlier this year on this “Libyan oily mess”, which shed lights on many suspicions around the faith of the Libyan oil, claiming in one statement that, ” many think, the move is a sign of the Beida government’s increasing intransigence, which has soured efforts by the UN to negotiate an end to the conflict and focus the fight on the Islamic State (IS). During peace talks last month (March ’14) Khalifa Haftar, a general allied to the Beida administration, ordered an air attack on Tripoli. General Haftar has received support from Egypt and the United Arab Emirates, which see Libya as a front in a war against Islamists (who are part of the alliance supporting the Tripoli government). But Western powers fear his war on “terrorists” is really an attempt to seize personal power. So although they recognise the Beida government, they have refused to enable its control of the country’s finances.”

Geneva talks had concluded primary agreements, yet the hope is always to turn words in conferences, into actions on the ground. Egypt sees the Libyan catastrophe as a major threat to its national security, and will not easily allow Islamists’ claims of territory along its western borders. Some regional and world powers have interests in keeping Libya the way it is, but the volatility of the international political scene is showing signs of conflicts, and modifications are best served in times of conflict.