Over the last decade, Africa’s trade volume with traditional partners doubled in nominal value. Africa’s overall trade volume has more than doubled however which explains why the share of traditional partners decreased. Africa’s trade with traditional partners remains crucial, however, at close to 62 per cent. The European Union still represents more than 40 per cent of Africa’s trade – the equivalent of $256 billion – and almost three times that of China.

As African countries strive to make the most of growing relations with the new economic forces, they need to be aware that their older partners remain a very solid and growing base. The downward trend of curves in the year 2009 should not be misunderstood. Africa’s trade is not structurally declining – on the contrary: the dip in 2009 reflects the onslaught of the financial crisis. Preliminary data for 2010 suggest that Africa’s trade has picked up for the old and new economic forces. Trade for the traditional partners is only decreasing in importance in relative terms and because of Africa’s very fast growth of trade with emerging partners.

As African countries strive to make the most of growing relations with the new economic forces, they need to be aware that their older partners remain a very solid and growing base. The downward trend of curves in the year 2009 should not be misunderstood. Africa’s trade is not structurally declining – on the contrary: the dip in 2009 reflects the onslaught of the financial crisis. Preliminary data for 2010 suggest that Africa’s trade has picked up for the old and new economic forces. Trade for the traditional partners is only decreasing in importance in relative terms and because of Africa’s very fast growth of trade with emerging partners.

In terms of foreign direct investment (FDI), the continued dominance of traditional partners is striking. OECD countries – including traditional partners – still account for about 80 per cent of FDI flows to Africa.

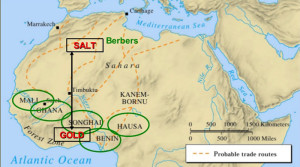

The sands of the Sahara Desert could’ve been a major obstacle to trade between Africa, Europe, and the East, but it was more like a sandy sea with ports of trade on either side. In the south were cities such as Timbuktu and Gao; in the north, cities such as Ghadames (in present-day Libya). From there goods traveled onto Europe, Arabia, India, and China.

Traders from North Africa shipped goods across the Sahara using large camel caravans — on average around a thousand camels, although there’s a record which mentions caravans travelling between Egypt and Sudan that had 12,000 camels.

The civilizations that flourished in ancient West Africa were all based on trade, so successful West African leaders tended to be peacemakers rather than warriors. Caravans from North Africa crossed the Sahara beginning in the seventh century of the Common Era. Traders exchanged gold for something the West Africans prized even more: salt. Salt was used as a flavoring, a food preservative, and as today, a means of retaining body moisture.

They brought in mainly luxury goods such as textiles, silks, beads, ceramics, ornamental weapons, and utensils. These were traded for gold, ivory, woods such as ebony, and agricultural products such as kola nuts (which act as a stimulant as they contain caffeine).

Salt was probably one of the earliest goods traded over long distances in Africa. While the vital mineral was scarce in the savanna and forest regions of Africa, large deposits of salt occurred in the Sahara. Those who controlled these deposits traded salt for slaves, gold, ivory, craft goods, malaguetta pepper, kola nuts, and foodstuffs from the forest and savanna zones. In turn, trans-Saharan traders purchased some of these goods, especially gold, ivory, slaves, and kola nuts, and carried them to North Africa. In exchange for these goods, caravans transported horses and Mediterranean craft goods, such as glass, south across the Sahara.

Salt mines in the Sahara produced large slabs of salt, weighing as much as 100 kg (220 lb), which porters transported by camel to central markets in cities such as Tombouctou, Mali. Slaves working in the enormous salt mines at Taghaza lived in houses and prayed in mosques constructed out of salt slabs. Another source of salt was the Songhai Empire, in present-day Mali, where salt functioned as currency. The kingdom’s rulers kept the location of salt deposits secret and heavily guarded. Canoes carried large quantities of cake salt from Gao up and down the Niger River and from river ports throughout West Africa. The mines of the Sahara were not the only source of salt. Kisama in Luanda, Angola, also produced significant amounts of salt. The Ijaw evaporated the seawater of the Niger Delta to produce salt in significant quantities. The kingdom of Bornu also exported salt that was produced by evaporating the saline waters of Lake Chad. Customers apparently preferred the taste of the lake salt, heavy in sodium carbonate, rather than pure rock salt for their millet porridge.