“We want to build our country, [but] we will not sell illusions to the people. With Allah’s will, by this time next year we will have finished the New Suez Canal project.”

When President Abdel-Fattah El-Sisi of Egypt announced that the digging of the New Suez Canal was to commence, he promised not only that it would be completed within a year, but that, as he said when he announced the project, it would become “a lifeline of prosperity to Egypt and the entire world.”

The timeline has been marked and the course of its progress followed step by step, beginning with the first cut in the ground and ending when water flowed through the new channel that now runs parallel to the first.

The festive atmosphere of the opening celebrations is the culmination of a whole year of digging, construction, finishing and waiting for the first drop of water to make its way through the new waterway. The Middle East Observer is highlighting the history of the great structure created by the Egyptian arms and muscles that built the old canal, and the initiative that was taken up again by the descendants of the labourers who toiled to launch the new canal.

File prepared by: Hind Abdel-Rahman

The canals of the two seas

The idea of digging a canal to link the Mediterranean with the Red Sea is not new, and what we have today is part of the priceless inheritance from our grandfathers, the ancient Egyptians who dug the first canal to link the Red and Mediterranean seas by way of the River Nile and its branches.

It was during the 12th Dynasty in 1874 BC that King Senusret III cut what we know as the Canal of the Pharaohs from the Red Sea to the River Nile, from where cargoes were ferried upriver to Thebes or downriver to Memphis and the north Egyptian coast. This canal eventually fell into disuse, but it was recut and renamed several times: under Seti I in 1310 BC; under Darius I in 510 BC; under Ptolemy II; under Emperor Trajan in 117 BC, when the Canal of the Romans was dug; and then under Amir al-Momeneen who cut from Fustat to Suez in the 640s after the Islamic conquest of Egypt by Amr Ibn al-Aas. The canal remained open for 150 years until the Abbasid caliph Abu Jaafar al-Mansour ordered it to be filled in to prevent supplies from Egypt reaching the people of Mecca and Madinah to support their revolution against Abbasid rule. After that the maritime road to India and the Orient was blocked, and commodities were transferred via desert convoys. The canal from the Red Sea to the River Nile remained closed until 1820.

With the discovery of the Cape of Good Hope, the movement of world trade changed. This had a negative effect on Egypt’s economy and commerce under the Mameluks, as it did on other commercial economies, such as that of Venice. The idea of digging a canal for trade and transport to link the Mediterranean and the Red Sea via the River Nile was revived and was presented to the princes of Venice through a delegation that visited Egypt so the idea could be explained to them. However, political conditions and Egypt’s conflict with the Ottomans prevented the execution of the project and it was shelved for many years. During this time several suggestions were put forward, such as one that the German philosopher Leibniz put to Louis XIV within the framework of a comprehensive project to conquer Egypt. Louis, however, feared angering the Ottoman Sultan and did not plan to carry out any expansion in the region.

The French campaign in Egypt in 1798 marked the first serious attempt to plan a canal route, which was made on direct orders by Napoleon Bonaparte. The idea was to dig a canal to link between the two seas (al-Bahrain), and Napoleon, along with his engineers, checked out the site. However one of the engineers, a man named Lauper, persuaded Napoleon to give up the project because he calculated the level of the Red Sea to be higher than that of the Mediterranean, and this, he said, would drown Egypt. Napoleon believed him.

The file was closed until 1832, when a party of engineering graduates came to Egypt and asked to visit the site. They concluded that the two seas were at exactly the same level and that the previous calculations were quite wrong. Muhammad Ali’s approval depended on two conditions, namely ensuring neutrality of the canal and, therefore, Egypt’s independence, and funding the canal from the Egyptian Treasury. Both conditions were turned down.

After Said Pasha came to power he formed a close relationship with the French diplomat Ferdinand de Lesseps, who had come to Egypt when his own family lost its fortune following the fall of the Napoleonic empire. De Lesseps presented a project for digging a canal to Said Pasha who, unlike his father Muhammad Ali Pasha, accepted it without precondition. Said Pasha obtained the approval of the Ottoman sultan and offered De Lesseps’ French company a 99-year concession. Thus the digging began.

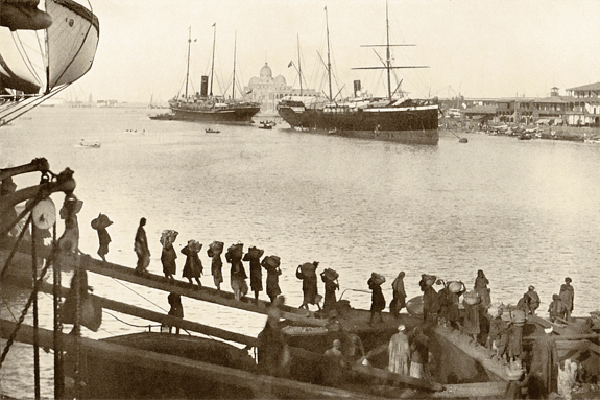

An opening fit for an empress

The Suez Canal opened in November 1869 with a lavish ceremony attended by an empress, kings, princes and princesses, men of literature, politics and art. Preparations for the big day started early. Six thousand guests arrived in Port Said, where the ceremony was to be held, at the invitation of Khedive Ismail and at the Khedive’s own expense. In the middle of the month, just prior to events, the Khedive, his courtiers and two ministers, namely Nubar Pasha and Sherif Pasha, travelled to Alexandria to board the yacht al-Mahrousa and sail to Port Said to welcome the guests arriving from all over the world. Cannons were fired as the guests arrived one by one, and ships from their countries were docked alongside the Egyptian fleet.

The ceremony began with a recitation of verses from the Holy Qur’an. Then the sheikh asked God that this great work would gain His blessings and care and would be rendered successful. After that Monsignor Corsia of Alexandria said a prayer in which he asked God to bless such good work. The ceremony was held on three large wooden stages set up on the beach and draped with silk, decorated with flags and flowers and covered with priceless carpets on which the chairs were lined up. The centre stage was reserved for guests, and here Khedive Ismail was seated with the guest of honour, Empress Eugenie of France, and Emperor Franz Joseph of Austria on either side. The stage on the right was earmarked for Muslim ulemas, led by Sheikh al-Mahdi al-Abbassi, the then Mufti of Egypt, while the left hand stage was for Christian clerics, led by Monsignor Corsia. On the Asian beach stood the horsemen of Port Said, while the African beach was covered with umbrellas for members of the public attending the ceremony. More than 80 ships were docked in a semi-circle along with 50 warships, including six Egyptian, six French, 12 British, seven Austrian, five German, one Russian, one Danish, two Dutch and two Spanish.

In the evening a delicious banquet was served, prepared by more than 500 chefs. At two o’clock lights and ornaments were seen along the canal, and the yacht Mahrousa appeared, surrounded by a halo of light. Cannons were fired every few minutes in harmony with music. The ceremony ended with fireworks at the dawn of the new day, when ships were admitted to transit the Suez Canal.

The deadly cost of the Suez Canal

The deadly cost of the Suez Canal

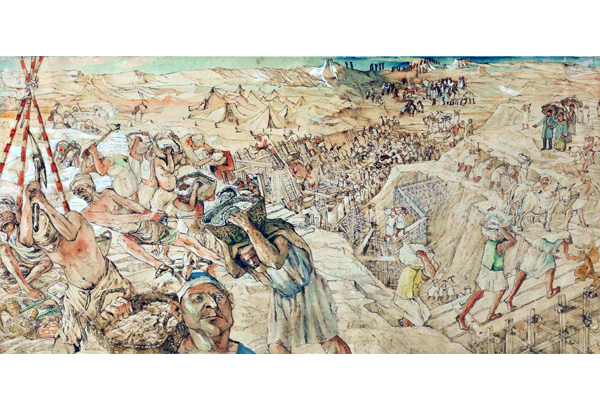

Hunger, thirst and high temperatures crushed their weak bodies; disease struck without warning; treatment was harsh and the work was tough. For 10 years Egyptian labourers struggled under the corvée to excavate the waterway thousands of them would never see.

More than 100,000 are said to have died, but the true number will never be known. Many of the bodies were buried under the desert sand or washed away by the water of the canal.

Ferdinand De Lesseps chose a French engineer to be responsible for the living conditions of the workmen, who were of different nationalities. However, the coercion, bad treatment and terrible conditions suffered by Egyptian peasants torn from their farms to labour for the International Suez Canal Company under the command of De Lesseps was unsurpassed. About a million Egyptian farmers were forced to leave their fields and villages and head for the desert to dig the canal.

De Lesseps drew up the list of work regulations, which was signed by Khedive Said. It stipulated the Egyptian government’s provision of all the labourers the company needed. It was therefore easy to add any number of men. De Lesseps set wages ranging from one and a half piastres to three piastres a day for those over 12 years of age. Younger workers only received one piastre. Each workman also received sun-dried bread.

The regulations included punishment of any workman who absconded and deduction of wages in case of any negligence seen by engineers. Despite the company’s promise to dig a sweet water canal for the labourers, this was never done and a large number died of thirst and under avalanches of sand. Disease and epidemics spread through the workforce. Some died of fatigue as they wielded axes, buckets and their own arms despite the fact that the company had promised to provide proper excavating equipment.

Said Pasha was no more merciful to the Egyptian workforce than the French. He visited the site in December 1861 and ordered that 20,000 more youths be mobilised to increase the rate of digging. The first few years of witnessed the largest number of forced recruits, with more than 22,000 compelled to join the workforce in one month. Those who declined to work or refused to follow orders were tracked down and tortured. Many of the workmen the Khedive chose were from Zagazig. He excluded youths with weak bodies and selected well-built young men who were sent to the canal area on foot, tied with ropes with only a bag of dried bread and a little water each.

Unfortunately these appalling scenes were of great interest to tourists, who came to watch them on their visits to the country. The company continued to inflict brutality on its Egyptian workmen. A medical division provided treatment for foreign workers, and according to medical reports held at the Alexandria municipality library most casualties suffered from bronchitis and other upper respiratory system diseases; conjunctivitis; dysentery; chickenpox; tuberculosis; liver disease and cholera, which killed a large number of labourers in 1865. A number of other unexpected factors also proved to be killers. One such was a liquid, clay-like material that surfaced during the digging and contained burning phosphorous.

Interestingly, the French government offered the French company’s medical team a medal of honour in 1867, claiming that they exerted efforts to save Egyptian labourers from death.

Story of ‘concession’

Story of ‘concession’

Said Pasha invited de Lesseps to pay him a visit, and on 7 November 1854 he landed at Alexandria; on the 30th of the same month Said Pasha signed the concession authorizing him to build the Suez Canal.

A first scheme, initiated by de Lesseps, was immediately drawn out by two French engineers who were in the Egyptian service, Louis Maurice Adolphe Linant de Bellefonds called “Linant Bey” and “Mougel Bey”.

“Ferdinand de Lesseps wrote to his friend and disciple, who loved to eat macaroni (Mohamed Saeed, who became the ruler of Egypt), and the Khedive invited him to visit Egypt where he was warmly welcomed. The ‘chief engineer’ convinced the Khedive that the canal would boost Egypt’s independence and immunity from the Ottomans. No single European power would be allowed to control the project, and it would be under the patronage of European countries combined. He also highlighted the personal glory Saeed would receive for building the Suez Canal. De Lesseps said the Canal would make Egypt a world trade hub between East and West, and would generate revenue and wealth many fold more than crops, including cotton.

“Thus, de Lesseps won sole concession to dig the Canal and established the Universal Company of the Suez Maritime Canal for this purpose, with a 10-year franchise that begins when the Canal is completed. All costs of constructing the Canal would be footed by the company, and then the Egyptian government would pocket 15 percent of the company’s annual profits, 10 percent would go to the founders, and the remaining 75 percent divided among shareholders.”

“When the company finished its studies, de Lesseps presented the study to Saeed Pacha and he signed the second concession contract dated 5 January 1856, ratifying the previous franchise to de Lesseps, including concessions to the company that were so flagrant no rational government seeking to protect the interests of the country would accept.”

These conditions included a waiver on the price of the land and buildings needed to build the seawater canal, freshwater canal, two branches for irrigation and drinking, and two kilometres on either bank of the canal. These were all tax exempted and the company had the right to annex land from individuals as necessary for construction, it also had mining rights at government mines and quarries for all construction and maintenance needs for free.

It also obligated land owners to receive a license from the company to irrigate their land in return for a fee. The concession was for 99 years and so digging of the Canal began on 25 April 1859.

“When Saeed died in 1863, Egypt had a debt of nearly eight million pounds sterling to be paid over 30 years, and another one million to be paid over three years, along with several short-term debts worth about nine million pounds sterling. The total sum of Egypt’s debt floating and fixed (ie short and long term) amounted to nearly 19 million pounds sterling when Saeed died, or nearly five times the revenue of the Egyptian government in the year prior to his death.”

Khedive Ismail (who succeeded Saeed) was shocked by the brazen concessions to the company, and began negotiations to ease them, most notably “reducing the number of labour the government must provide to the company to 6,000 because the current number (at 20,000) harms the country and agriculture. Also, increasing their wages to two francs a day per worker,” and cancelling the company’s land concession. The company objected and sought arbitration in France which ruled against Egypt and fined it 3.36 million pounds, or almost half the capital of the company. “Thus, all the phases of the project since the beginning until after its completion were disastrous for the country.”

“Thirteen years after Ismail’s reign, in 1876 the year when Egypt lost control of its financial administration which came under the control of foreign financial monitors, Egypt’s foreign debt reached 91 million pounds.”

“In 1875, European bankers declared Egypt bankrupt. Ismail sold Egypt’s shares in the Suez Canal to pay back debts, which were mostly bought by British Prime Minister Disraeli with a loan from the Rothschild family. Thus, Britain became the largest shareholder of the Canal, owning 44 per cent of shares. Disraeli told Queen Victoria the news: ‘The Canal is now yours, majesty. Egypt’s share is no more than 15 per cent of profits which generates no more than one million francs annually.’ Soon France bought this right from his successor Khedive Tawfiq, and so Egypt lost its entire share in the Canal.” In 1881 “the British defeated Orabi’s troops at Tal Al-Kabir battle and Britain occupied the Suez Canal region and declared Egypt a protectorate.”

According to Abdel-Rahman Al-Raf’ie, Egypt Endeavours in Modern History: From the reign of Mohamed Ali until Saeed.

Paying the price, then and now

Paying the price, then and now

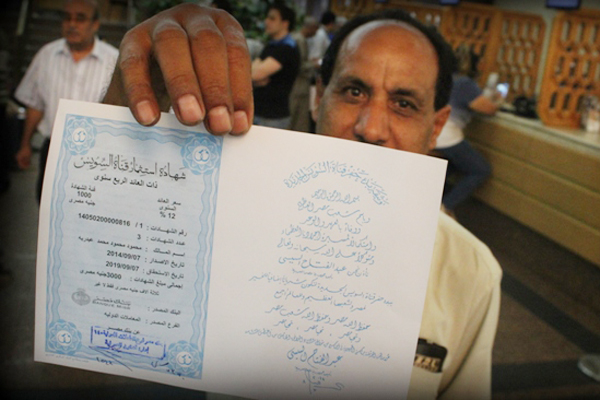

The New Suez Canal project has proven that the conquering spirit of the Egyptians and their sacrifices will never cease. While they paid to construct the original canal with their sweat, their blood and their lives, so the people have turned out their pockets and used their own money to pay for the new one.

Together they raised billions of pounds within just a few days of Prime Minister Ibrahim Mahlab’s offering Suez Canal investment certificate in denominations of LE10, LE100 and LE1,000. Sixty billion Egyptian pounds were collected to fund the project. The one condition was that the certificates be sold only to Egyptians at an annual interest rate of 12 per cent, to be paid every quarter.

The people rallied to support the project and to prove wrong all those who doubted their response. The Governor of the Central Bank of Egypt declared on 15 September 2014 that the proceeds from the sale of the Suez Canal investment certificates had exceeded the required amount to reach about LE64 billion since the beginning of the launch on 4 September. Purchases by individuals amounted to 82 per cent, while purchases by companies and institutions came to only 12 per cent. It was then decided to close the public offering of the certificates at banks.

Money was not the only price paid by Egyptians for the new canal, since the participating workers played a prominent role in the completion of the project on schedule which cost them their comfort, time and even some lives. Sadly there were individual incidents, such as when one of the workmen lost his balance and fell on his head. Even so, the number of fatalities can never be compared with the loss of life when the original canal was built. Nevertheless both the past and present canal projects have proved that the Egyptians aspire for a better future, whatever the cost.

Nasser’s rallying cry and the Suez Crisis

Nasser’s rallying cry and the Suez Crisis

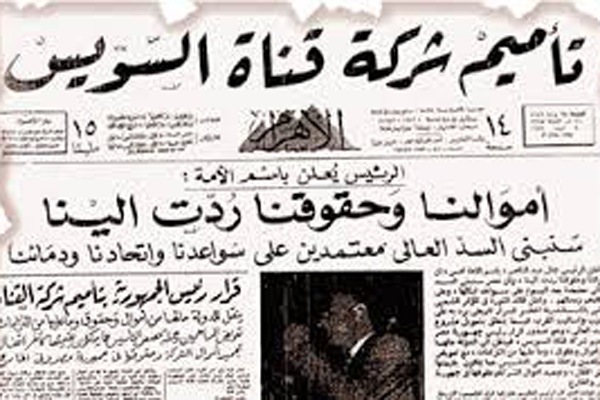

“In the name of the nation, in a decision by the President of the Republic… the International Suez Canal Company has been nationalised to become an Egyptian joint stock company.”

Who can forget the powerful cry uttered in the commanding tone of President Gamal Abdel-Nasser? Its echo still resounds in our ears, and we can even hear the subsequent cheers and applause.

The challenging cry was preceded by a period of acquiescence and acceptance of the terms of foreign concession, which was scheduled to end in 2008 under the terms of an attempt to extend it for another 40 years. It was originally due to expire in November 1968, but the British government saw the need to extend the concession after traffic in the canal increased dramatically. The terms of the concession stipulated the division of net profits equally between the company and the Egyptian government. However, if profits reached less than 100 million francs, the Suez Canal Company would take 50 million francs and the Egyptian government would receive only the remainder. If the revenue were 50 million francs or less, then the government received nothing.

The Egyptian national movement, led by Muhammad Farid attacked the proposal, and economist Talaat Harb explained the amount of losses to Egypt if the concession were extended. Under public pressure the General Assembly assigned Harb and Samir Sabry with writing a report on the subject, upon which the company’s concession was rejected and the concession remained on its own terms.

On 26 July 1956, the day Nasser announced the decision to nationalise the canal company as an act of Egyptian sovereignty, the beneficiaries’ body of the canal withdrew its foreign guides to prove that Egypt would not be able to manage the canal on its own. The first response came from France and the United Kingdom, who froze Egyptian assets in their respective countries. The Egyptian government had a credit account in England worth about £135 million sterling, and additionally Switzerland was asked to cooperate in pressurising Egypt by freezing its Egyptian funds. The United States froze the funds of the Canal Company as well as its Egyptian government funds until matters were clear as regards the future of the Suez Canal Company. The government’s funds were estimated at about US$43 million. The United States even announced it would halt any financial or technical assistance to Egypt.

The Director of the Canal Company also instigated all unions of ship owners to pay their canal tolls to the company and not to the Egyptian government. Indeed, the total amount of fees received by the Egyptian government from the nationalisation until the closure of the canal was 35 per cent. The rest went to the Suez Canal Company.

Attempts began to mobilise international public opinion against Nasser’s decision and to accuse Egypt of opposing the principle of freedom of transit in the canal and of threatening peace in the region. The foreign ministers of France, the UK and the US met and issued a statement to this effect. They pointed to the provisions of the Constantinople Convention signed by a number of nations in October 1888 which stipulated freedom of navigation of the canal, recognised the sovereignty of Egypt of the canal and committed world states to respect the safety of the canal and refrain from any military operations in it. The real fist on the canal, however, remained with France, which still controlled the majority of shares in the canal company. France called for a conference of beneficiaries of the canal as well as the signatories of the convention. The US proposal won a majority vote. It included a project to establish an international organisation to oversee the management of the canal, but this was opposed by some countries and rejected by Nasser. This situation forced the British Prime Minister to declare the establishment of a new body on behalf of the beneficiaries’ body to be responsible for traffic coordination in the canal and the collection of fees.

The Security Council issued a resolution in October 1956 of six principles to be the basis for negotiations that should take place in the future. It also included the recognition of the beneficiaries’ body that would be charged with overseeing the canal. However, it only gained nine votes and the objection of two votes including the Soviet Union, which had power of veto. This forced Europe and the US to think about military pressure after diplomatic negotiations had failed.

The result was the tripartite aggression or Suez War as it called by the West, under the pretext of protecting navigation in the canal. In turn, Egypt immediately announced that it could not agree to the occupation of the canal province and informed the Security Council of this. However, the use of Great Britain and France of their veto prevented the council from action. The British-French attack on Egypt began on one front and the Israeli attack on the other, so Nasser ordered the withdrawal of Egyptian troops from Sinai to the west of the Suez. The fighting remained fierce until the United Nations General Assembly issued a decision to stop the fighting on 2 November, which Egypt accepted. Britain, France and Israel rejected it, however, until the Soviet Union gave Britain and France an ultimatum to end the aggression. Threats by other nations eventually led to stopping the British-French incursion, accepting a ceasefire, withdrawing troops and clearing the canal.

Completed in just one year

Completed in just one year

The world’s dredgers help dig the new canal, with revenues expected to shoot up to US$13.4bn by 2023

From 10 years to one year, and from 190 kilometres to 72 kilometres of dry drilling and 37 kilometres of broadening and deepening the original canal. From labourers forced to dig by hand with axes, to employing roughly 45 dredgers —75 per cent of the world’s dredgers—to raise millions of cubic metres. These and other differences between the two Suez canals reveal the extent of the huge achievement of completing this task in just a year. Raising more than 250 million cubic metres of dry sand and 250 million cubic metres of water-saturated sand in the largest dredging operation in history—and, we say it again, it only took a year.

With the help of a vast amount of equipment—more than 4,800 loaders, drillers, dump trucks and lorries to transport the sand—23 channels for connecting power cables, water and gas to the eastern part of the canal have been completed. There is a main station to monitor ships and electronic navigation. There are three quays for passengers on the new waterway, and eight new ferries, each with a 320-ton load, to update the Suez Canal Authority’s ferryboat fleet and improve the service to passengers crossing between the eastern and western banks. A total of 110 of the latest type of buoy will send signals to ship captains with information on the movement of tides and sea currents. Nearly 460 of 3,828 targeted basins have been drilled within the framework of an aquaculture project to help provide food security for Egyptians.

The Armed Forces Engineering Department has been in charge of supervising the project, along with the Suez Canal Authority. The dredging was carried out by two consortiums of alliances of American, UAE, Dutch and Belgian companies. The highest dredging rates reached 41 million cubic metres per month. Some 84 civilian companies have helped in the project, along with roads and mine-sweeping battalions.

The Dar al-Handassa consortium won the contract for preparing the general plan for the project of the Suez Canal axis development out of 14 applicants for the tender conducted by the Suez Canal Authority.

The canal will realise a non-stop direct transit benefit for 45 ships in both directions with the possibility of allowing for the transit of vessels of up to 66 feet in every part of the canal, bringing expected revenues in 2023 to US$13.4bn compared with the current US$5.3bn. Transit time will also be reduced, as well as the standby time for ships which will now wait for three hours instead of the previous eight or more hours. This will contribute to increasing the demand for using the canal as a main navigation waterway. The Armed Forces’ Engineering Department has begun to operate a floating bridge on the canal at Sharq al-Qantara from 11am until noon.

A trial operation began on 25 July in order to ensure that the canal was ready to operate as planned.